Vectors in AI: Definition, use cases, and practical examples

Post Date : 2025-10-28T08:05:32+07:00

Modified Date : 2025-10-28T08:05:32+07:00

Category: AI

Tags: artificial-intelligence

In machine learning, vector is an array of numbers use to reflect the features. The target is transforming complex data structure like text, images, audios to numbers that a computer program can compare.

In math or physic, vector is a quantity that has both size (magnitude) and direction.

Problem & Solution

We are going to build a chatbot system to enhance user experience. Let’s take a look at this use case.

The food store serves the following foods and drinks:

- Bread and fried eggs

- Pho Noodle (Vietnamese noodle)

- Coffee

- Tea

- Coca

- Bun Noodle (Vietnamese noodle)

A bot ask user: What do you like for this morning? User respond: I want something soupy

So what should the system respond in this case, if you are a server(waiter/waitress), you can easily suggest Pho Noodle, Bun Noodle. But if it is a computer program, how to do that?

This is where we can use vector to solve this problem by using semantic search and features not a text matching search algorithm.

How do vector work in this scenario ?

Example:

The sentence “Tôi thích ăn phở” is converted into a 384-dimensional vector. The sentence “Tôi mê phở bò lắm” is converted into another 384-dimensional vector.

→ If the two sentences have similar meaning, their vectors will be positioned close to each other in vector space.

To formalize the notion of “closeness,” we use similarity or distance metrics. Common metrics include:

- dot product

- cosine similarity

- Euclidean distance

So that to allow the computer program can compare distance between 2 vectors (use search and the data), all data must be transformed into multi dimensional vector. That technique is called “Embedding”.

Embedding

An embedding is a technique for representing objects (such as text or images) as numerical vectors in a multi-dimensional space. This allows a machine to capture and reason about their meaning and relationships. These representations are learned automatically during training, enabling more efficient processing of complex information in tasks such as semantic search, classification, and recommendation.

Why does embedding-based search work?

An embedding maps a sentence or passage of text into a high-dimensional vector (e.g. 384, 768, or 1536 dimensions, depending on the model).

These dimensions are learned in such a way that:

- Texts with similar meaning produce vectors that are close to each other.

- Texts with different meaning produce vectors that are far apart.

- This property is known as “semantic similarity in high-dimensional space.”

Example:

Query: “how to fix iPhone battery draining fast” Document A: “troubleshooting steps to reduce iPhone battery drain” Document B: “discount iPhone fast chargers available now”

A standard keyword search may return both documents, since they both contain terms like “iPhone” and “battery.” However, an embedding-based search can identify that Document A is semantically relevant to the user’s intent (diagnosing and fixing battery drain), whereas Document B is focused on purchasing accessories, which does not address the underlying issue.

=> This is why semantic search is often more effective than pure keyword matching.

Dot product (tích vô hướng)

Assume we have two vectors of the same dimension:

a = [a₁, a₂, …, aₙ] b = [b₁, b₂, …, bₙ]

The dot product is defined as: a · b = a₁×b₁ + a₂×b₂ + … + aₙ×bₙ

Intuition:

- If a and b point in a similar direction, the dot product is large (positive).

- If a and b point in opposite directions, the dot product is negative.

- If they are orthogonal (unrelated), the dot product is approximately 0.

Cosine similarity ( độ tương đồng cosine )

Bản chất là đo góc giữa 2 vector chứ không quan tâm độ lớn

Cosine similarity measures the angle between two vectors, rather than their absolute magnitudes.

The formula is:

cosine_sim(a, b) = (a · b) / (‖a‖ × ‖b‖)

Where:

- a · b is the dot product

- ‖a‖ is the length (magnitude) of vector a, defined as sqrt(a₁² + a₂² + … + aₙ²)

Interpretation:

- 1 → the two vectors point in exactly the same direction (high semantic similarity)

- 0 → the vectors are unrelated / orthogonal

- -1 → the two vectors point in opposite directions (opposite meaning)

Because cosine similarity focuses only on the angle between vectors, it is widely used to measure semantic similarity between two sentences after they have been embedded.

Basic text representation

Tokenization is the process of splitting a sentence into smaller units called tokens.

In the simplest form, we can split by whitespace: “Tôi thích ăn phở bò” → [“Tôi”, “thích”, “ăn”, “phở”, “bò”]

Modern language models, however, use more advanced tokenizers that can break words into subword units. This allows the model to handle rare or unseen words by decomposing them into smaller meaningful parts.

Stop-word removal

Stop words are very common words that typically carry low discriminative value, such as:

English: “the”, “is”, “and”, “of”

Vietnamese: “là”, “và”, “của”, “thì”, “lúc đó”, “cái này”, …

In traditional approaches like Bag-of-Words (BoW) and TF-IDF, these words are often removed to reduce noise.

Note: In modern embedding-based systems, manual stop-word removal is usually unnecessary because the model implicitly down-weights those words.

Bag-of-Words (BoW)

Core idea:

Count how many times each word appears.

Ignore word order entirely.

Consider the two sentences:

- “tôi thích phở bò”

- “phở bò ngon, tôi rất thích”

Shared vocabulary = [“tôi”,“thích”,“phở”,“bò”,“ngon”,“rất”]

Their BoW representations (following the vocabulary order above) are:

- Sentence 1 → [1,1,1,1,0,0]

- Sentence 2 → [1,1,1,1,1,1]

Advantages:

- Simple and easy to compute.

Limitations:

- It does not capture context (for example, “bò” could mean “beef” or “cow”).

- It does not capture synonymy (“ngon” and “tuyệt vời” express similar sentiment but are treated as different words).

TF-IDF

TF-IDF stands for Term Frequency – Inverse Document Frequency.

Intuition:

- Term Frequency (TF): how often a term appears in a given document.

- Inverse Document Frequency (IDF): how rare that term is across the entire collection of documents.

In practice:

- High TF → the term is important for that specific document.

- High IDF → the term is rare elsewhere, so it helps distinguish that document from others.

For example:

- A term like “phở” may appear frequently only in a few documents → high IDF → considered important.

- A term like “và” appears in almost every document → low IDF → low value.

Compared to BoW, TF-IDF improves relevance by down-weighting extremely common words.

However, TF-IDF is still fundamentally keyword matching. It does not truly understand meaning or semantic relationships.

Keyword Search vs. Semantic Search

Keyword search (BoW / TF-IDF / BM25):

- Keyword-based retrieval relies on explicit term matching.

- It performs well when the query requires an exact phrase or technical term, such as debugging an error message: “TypeError: cannot read property ‘map’ of undefined”.

- However, it becomes less effective when the user expresses the same intent using different wording, for example: “nhà hàng chay” (“vegetarian restaurant”) vs. “quán cơm chay lành mạnh” (“healthy vegetarian rice place”).

Semantic search (Embedding + Cosine similarity):

- Semantic search relies on meaning rather than exact word overlap.

- It can still retrieve relevant documents even when the wording in the query does not match the wording in the document.

- This approach is especially effective for natural-language questions, FAQs, internal chatbots, and RAG pipelines.

=> In a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system, semantic search is typically used to retrieve the most relevant context for the language model.

Evaluation Metrics

Suppose you have an information retrieval system. A user submits a query, and the system returns a ranked list of documents (top K). You now want to evaluate: “Did we retrieve the relevant documents?”

The standard metrics are precision, recall, and F1.

Precision

Precision answers the question: Of all the documents the system returned, how many were actually relevant?

Formula:

Precision = (number of relevant documents retrieved) / (total number of documents retrieved)

Example:

The system returns 5 documents, and 3 of them are truly relevant. → Precision = 3 / 5 = 0.6 (60%)

High precision means the system returns very little noise.

Recall

Recall answers the question: Out of all the relevant documents that exist, how many did the system manage to retrieve?

Formula:

Recall = (number of relevant documents retrieved) / (total number of relevant documents in the entire dataset)

Example:

There are 6 relevant documents in the entire corpus. Your system returns 3 of them. → Recall = 3 / 6 = 0.5 (50%)

High recall means the system is not missing important documents.

Precision vs. Recall

High precision with low recall means the system is very strict: it only returns what it’s confident about. The results are clean, but it may miss many relevant documents.

High recall with low precision means the system returns a lot: it captures most of the relevant material, but it also brings in a lot of irrelevant content.

Which one matters more depends on the use case:

For sensitive assistants (e.g. legal or medical chatbots), high precision is critical, because returning wrong or misleading content is dangerous.

For discovery or research pipelines where humans will review results later, high recall is often preferred, because missing relevant evidence is costly.

F1-score

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It balances both.

Formula:

F1 = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall)

A high F1-score indicates that the system is both accurate (high precision) and comprehensive (high recall).

Examples

Tokenization

from transformers import GPT2Tokenizer

def observe_tokenization(text):

tokenizer = GPT2Tokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

ids = tokenizer.encode(text)

print("Tokens:", tokens)

print("Token IDs:", ids)

print("Decoded back:", tokenizer.decode(ids))

Similarity

Imagine each number in the vector is a feature of an animal. For example:

- Feature 1: number of legs

- Feature 2: how “friendly/close to humans” it is (1 = not very, 3 = more familiar, 10 = an elephant… which is kind of its own thing 🐘)

- Feature 3: relative size / body mass

(This is just for illustration, not real scientific data.)

Now we want to ask: which animals are the most similar to each other?

cat = [4, 1, 3]

dog = [4, 1, 4]

elephant = [4, 3, 10]

# A⋅B=a1×b1+a2×b2+a3×b3

cat = [4, 1, 3]

dog = [4, 1, 4]

dot_product_cat_and_dog = 4*4 + 1 * 1 + 3*4 = 29

cat = [4, 1, 3]

elephant = [4, 3, 10]

dot_product_cat_and_elephant = 4*4 + 1 * 3 + 3*10 = 49

dog = [4, 1, 4]

elephant = [4, 3, 10]

dot_product_dog_and_elephant = 4*4 + 1 * 3 + 4*10 = 59

# ∥A∥=a12+a22+a32

‖cat‖ với cat = [4, 1, 3]

‖cat‖ = √26

‖dog‖ với dog = [4, 1, 4]

‖dog‖ = √33

‖elephant‖ với elephant = [4, 3, 10]

‖elephant‖ = √125

cos(θ)= (A*B) / (‖A‖*‖B‖)

Cosine(cat, dog) = 0.9900

Cosine(cat, elephant) = 0.8595

Cosine(dog,elephant) = 0.9186

cosine_similarity expects the input to be in the shape (n_samples, n_features), meaning a 2D matrix.

cat.reshape(1, -1) = 1 sample = the cat dog.reshape(1, -1) = 1 sample = the dog

If you just pass a 1D vector like [4, 1, 3] directly, it might throw an error.

Terminologies

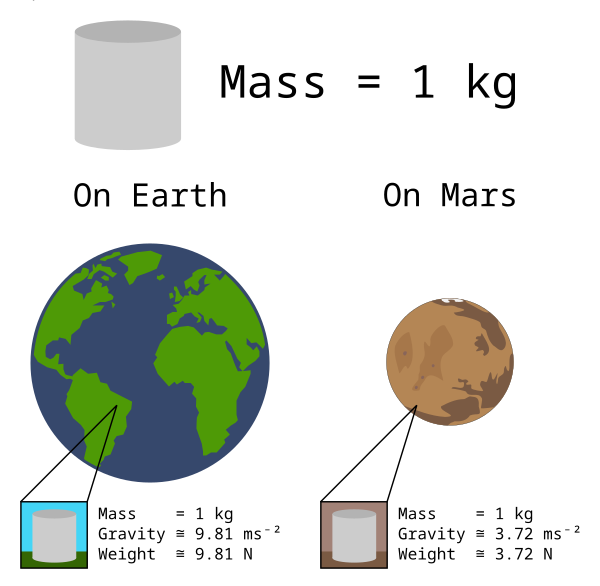

Scalar: something that has size (magnitude) but no direction: length (độ dài), area (diện tích), volume (thể tích), speed (tốc độ), mass (khối lượng), density (mật độ), pressure (áp suất), temperature (nhiệt độ), energy (năng lượng), entropy, work (công), power (công suất)

Vector: a quantity that has both size (magnitude) and direction: displacement ( độ dời ), velocity (vận tốc), acceleration (gia tốc), momentum (động lượng), force(lực), lift(lực nâng), drag(lực cản), thrust(lực đẩy), weight(trọng lượng)

Images

Mass, Weight

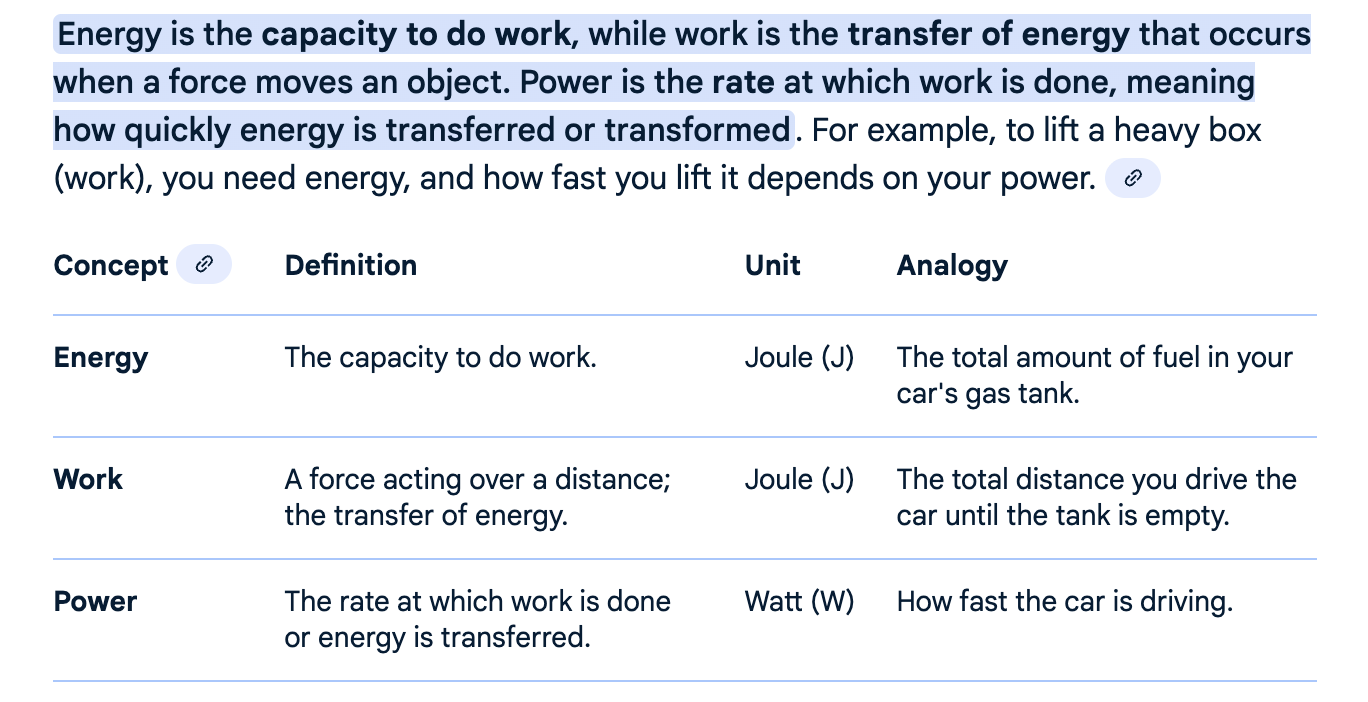

Energy, Work, Power